The Tech Behind Eon: Tooling!

The Tech Behind Eon: Tooling

Eon represents four years of work and during this we made several iterations to various tools and pipelines. I’ll save the 3D scene packer and track loader for separate posts, but this post will cover the other aspects of our pipeline.

Code Builds

First things first: we use cross-compilation. Our build environment works on Mac, Linux and Windows and produces both ADF floppy images and stand-alone test programs, as well as a multitude of host tools. This section will cover some of the details of our setup, as well as some history.

We started with a stripped down, assembly-only version of our A1200 demo system (called NewAge for some reason). We got rid of all the C code and simplified things down to the very basics. This is how early prototyping of things like the rubber cube started, in plain 68k assembly.

Build System origins

We were already using Tundra as our build system, which is a great choice for us as it supports complicated cross-platform builds, it’s fast, robust and extensible, and, well, I wrote it so we have a pretty good understanding of how to use it.

One of the things we wanted early on was a way to generate some boilerplate

code automatically, like generating a lookup table during build time. The first

attempt at this was a Lua-based frontend to the assembler which ran as a

prepass, so you could “escape” into Lua to generate a bunch of assembly. While

this got the job done, it was problematic for a number of reasons, and the

biggest problem was that you had no idea what actual source line a piece of

assembly came from. For example, if you had generated a lookup table of 1,024

dc.w statements, all the subsequent assembler error messages might be offset

by hundreds of lines and you’d have to go rummage through the generated

assembly (in the output directory) to figure out what you did wrong.

Unsatisified with this state of affairs, we cloned

vasm and made a few modifications so we

could use something similar to C preprocessor #line directives. The assembler

would then point back to the original source code, and things were OK for a

while.

Deluxe68

The Lua preprocessor thing we had didn’t actually solve the hardest problem with maintaining a large assembly codebase, which is the cognitive load of making changes to older code. We kept trashing registers and screwing with calling conventions and tracking all this down in the emulator is a pain to say the least. Often these bugs were introduced because the programmer missed the fact that some register was precious or already in use, and would only manifest occasionally.

We also weren’t really using the “macro” part of the Lua preprocessor as much as we had anticipated, because we were already building data in a separate pipeline and most of the demo was art driven and not code driven.

I took a stab at solving the maintainability problem, and the result was

deluxe68 which is a different

kind of assembly preprocessor (again leveraging our #line directive

vasm feature). Deluxe68 is a simple kind of register allocator that complains

if you make mistakes with your registers. The tool evolved a little bit over

the years, but it has essentially stayed true to this single purpose.

The way it works is that you use symbolic names for registers, and the tool

will allocate and free those registers from a register pool automatically.

It also has limited support for spilling and restoring registers, as well

as reserving some registers from the pool (like a6) so you can use them

for hardwired ABI purposes or other things.

With this tool in hand we ported almost all our plain assembly code to this

style of programming and we were very pleased with the results. It’s much

easier to make changes and not break things, because d68 will automatically

save and restore modified registers (generating movem.l sequences) for you.

Here is an example routine from the demo so you can get a sense of what the code looks like:

XDEF ScenePlayerDecompressBitplaneMasks

@proc ScenePlayerDecompressBitplaneMasks (a6:statep)

IFGT SP_PROFILE_LEVEL-0

TBL_BEGIN_SCOPE "ScenePlayerDecompressBitplaneMasks"

ENDC

; Fetch count of bitplane masks

@areg countp

move.l SP_COUNT_PTR(@statep),@countp

@dreg bitplane_masks_count

move.b (@countp)+,@bitplane_masks_count

lsl.w #8,@bitplane_masks_count

move.b (@countp)+,@bitplane_masks_count

move.l @countp,SP_COUNT_PTR(@statep)

@kill countp

IFNE SP_PRINTF_DEBUG

Printf "Num bitplane masks: %lx",@bitplane_masks_count

ENDC

; Decompress bitplane masks

tst.w @bitplane_masks_count

beq.s .noBitplaneMasks

@reserve d0,a0-a1

lea SP_3BIT_DECODERSTATE(@statep),a0

lea SP_BITPLANEMASKS(@statep),a1

move.w @bitplane_masks_count,d0

bsr DecodeBitStream_3Bits_Words_Decode

@unreserve d0,a0-a1

.noBitplaneMasks

@kill bitplane_masks_count

IFGT SP_PROFILE_LEVEL-0

TBL_END_SCOPE

ENDC

@endproc

And here is what comes out from deluxe68. Note the use of tbl_line directives

to point back to the original source file, as well as the automatic register

preserving that has been inserted:

XDEF ScenePlayerDecompressBitplaneMasks

; @proc ScenePlayerDecompressBitplaneMasks (a6:statep)

; live reg a6 => statep

ScenePlayerDecompressBitplaneMasks:

movem.l d0/d7/a0/a5,-(sp)

tbl_line 396 /Users/dep/repo/newage_a500/Engine/A500/ScenePlayer/ScenePlayer.d68

IFGT SP_PROFILE_LEVEL-0

TBL_BEGIN_SCOPE "ScenePlayerDecompressBitplaneMasks"

ENDC

; Fetch count of bitplane masks

; @areg countp

; live reg a5 => countp

tbl_line 404 /Users/dep/repo/newage_a500/Engine/A500/ScenePlayer/ScenePlayer.d68

move.l SP_COUNT_PTR(a6),a5

; @dreg bitplane_masks_count

; live reg d7 => bitplane_masks_count

tbl_line 407 /Users/dep/repo/newage_a500/Engine/A500/ScenePlayer/ScenePlayer.d68

move.b (a5)+,d7

lsl.w #8,d7

move.b (a5)+,d7

move.l a5,SP_COUNT_PTR(a6)

; @kill countp

IFNE SP_PRINTF_DEBUG

Printf "Num bitplane masks: %lx",d7

ENDC

; Decompress bitplane masks

tst.w d7

beq.s .noBitplaneMasks

; @reserve d0,a0-a1

lea SP_3BIT_DECODERSTATE(a6),a0

lea SP_BITPLANEMASKS(a6),a1

move.w d7,d0

bsr DecodeBitStream_3Bits_Words_Decode

; @unreserve d0,a0-a1

.noBitplaneMasks

; @kill bitplane_masks_count

IFGT SP_PROFILE_LEVEL-0

TBL_END_SCOPE

ENDC

; @endproc

movem.l (sp)+,d0/d7/a0/a5

rts

tbl_line 438 /Users/dep/repo/newage_a500/Engine/A500/ScenePlayer/ScenePlayer.d68

tbllink

At the end of the project we were facing some problems that were hard to tackle. The individual parts are HUNK executables that our layout tool strips and lays out on the floppy for the final demo. We had been using vlink for this, and things were mostly working fine.

However, we needed one “killer feature” that we couldn’t really get with vlink. We wanted “uninitialized bss”, which is not zero-initialized by the loader. This means that it’s garbage at runtime, but that’s fine for things you’re going to clear and render to anyway! On a background processing loader like our streamer just clearing all these large BSS buffers can be a significant time waster.

We were also unhappy with the debug information we could get out of vlink–we wanted all symbols (including local ones) for tools that I’ll describe later.

So I sat down and wrote a custom linker to replace vlink so we could have these features. In the end it was a very quick job (just a few nights) and I was surprised how little code it was in the end.

A return to C

About 18 months before we shipped the demo we had amassed a lot of individual programs that made up the parts. While they shared code where possible, there was still a lot of boilerplate to write. It’s also unnecessary to write “artsy” parts in assembly. Most of the high-level code in each part just kicks off a few blits or calls out to highly optimized routines for 3D.

So we explored various options for C compilation. We discarded VBCC as we weren’t happy with the code generation in many cases, and we had to fix plenty of bugs in it when we shipped A1200 demos.

We ended up making a slightly custom build of bebbo’s GCC port. We simply changed the ABI to use more registers to make function calls quicker.

For example, here is the high-level init code for one of the parts:

static void Part_init() {

CopperList_set_bitplanes(s_copperlist_template.bitplanes, &g_i2f_image, I2F_IMAGE_DEPTH, I2F_IMAGE_BPLSIZE);

CopperList_set_palette(s_copperlist_template.colors, (u16*)&g_i2f_image[I2F_IMAGE_SIZE], I2F_IMAGE_COLORS);

UAEMemProtect(g_morph_data, 9852, MEMPF_READ);

// set upper colors to white for bitplane 5

for (u16 i = 16; i < 32; ++i) {

s_copperlist_template.colors[i].data = 0xfff;

}

_Static_assert((I2F_IMAGE_BPLSIZE * 3) < SHARED_SCREEN_SIZE, "ImageToFlatNew: Out of shared screen memory");

u8* shared_buffer = DemoSys_get_shared_screen();

s_render_buffers[0] = shared_buffer;

s_render_buffers[1] = shared_buffer + I2F_IMAGE_BPLSIZE;

s_fill_scratch = shared_buffer + (I2F_IMAGE_BPLSIZE * 3);

DoubleCopper_create(

(CopperListInstruction*)s_copper_list,

(CopperListInstruction*)&s_copperlist_template,

COPPER_SIZE,

sizeof(s_copperlist_template));

Sprites_disable();

ImageToFlat_init(

&s_morph_state,

g_morph_data,

SCREEN_WIDTH / 8,

I2F_IMAGE_BPLSIZE,

15, 7, 0);

ImageToFlat_update(&s_morph_state);

ImageToFlat_step_active(&s_morph_state);

MulTable_generate(s_lines_mul_table, SCREEN_WIDTH / 8, I2F_IMAGE_HEIGHT);

}

This ended up working great. We had to write some glue inline assembly to expose

certain m68k opcodes that GCC refuses to generate, but in the end it was a solid

win. For example, here is how we generate a swap instruction where needed:

u32 inline m68k_swap(u32 value) {

asm volatile ("swap %0" : "=d" (value) : "0" (value));

return value;

}

We also wrote a preprocessor that enables us to include binary files in C, with full dependency tracking in the build system. This makes it super convenient to just drop in statements like these:

INCBIN_CHIPMEM(u8, g_i2f_image, "Output/ImageToFlat/ImageToFlatPart1_Background_Indexed_16Colors.bin");

INCBIN(u8, g_morph_data, "Output/ImageToFlat/image_to_flat.bin");

We generate an assembly file from these statements using a simple python script, and that assembly file is then compiled separately.

fs-uae

One of the best technical choices we made during the project was to build our own emulator from source, and make it a first-class citizen of the code build system.

This means we can make changes to the emulator as we see fit and it will automatically rebuild for us when we kick our demo off.

First we had to find a version of UAE that would actually work on all platforms. It turns out fs-uae is basically the only one that does, but it comes with significant build baggage on Windows, and doesn’t build with MSVC out of the box. So the first task was to port the emulator to MSVC code, including dependencies like glib and other stuff that was needed.

Once that was done we could move on to the features we were eyeing..

Warp

Whenever you boot something in the emulator to test it, it’s slow. You can

manually hit F12+W to enable warp mode, but you have to remember to turn it

off again, and that makes it hard to see what happens on the first frame of the

effect you’re testing.

So the very first thing we did was add a calltrap to control the UAE warp mode from the Amiga side. We start the emulator in Warp mode, and have the startup code turn it off. This easily saved 10 seconds of iteration time whenever we kicked something off.

But that was just the start..

Emulator printf

The next thing I added was a calltrap to have the emulator format out a bunch of data from the Amiga side in a printf format and dump that to the console.

On the assembly side we have a Printf macro that pushes parameters to the

stack (in our debug configuration) and then traps into the emulator with a

simple jsr $ff0fxx. This is nice because it’s much faster than doing it

on the Amiga side by calling something like exec’s RawDoFmt.

With this feature, it is super cheap to add diagnostics at bootup that only show up in the debugging config in the emulator, and doesn’t slow things down at all. We can print stuff 100s of times per frame without slowing things down noticably. Starting up the demo on our emulator, the log shows something like this:

res_initcode context = 0x0

[ 0.00000] Running under UAE.

TBL setwarp: 0

[ 0.02857] Disabling caches

[ 0.02869] Standalone loader initializing

[ 0.02881] Calling entrypoint with sp=<0021bee4>

[ 0.02886] Loader: chip_base = <00010ef8>

[ 0.02888] Loader: fast_base = <003d4e00>

[ 0.02889] Loader: loader_size = 0

[ 0.02889] Loader: tab_dsk_len = 0

[ 0.02890] Loader: loader table = <00226058>

[ 0.02891] Loader: floppy0 adj = 4828

[ 0.02893] Loader: stacks_end=<003d4e00>

[ 0.02895] Loader: loader fast base = 003d4e00 - 00452e00, 516096 bytes

[ 0.02896] Loader: loader chip base = 00010ef8 - 00097e58, 552800 bytes

[ 0.02898] Loader: ldr_alloc_permanent: grab 100800 bytes for sharedscreen (chip); remain=452000

[ 0.02899] Loader: SharedScreen Chip at 00010ef8 - 000298b8

[ 0.02900] Loader: ldr_alloc_permanent: grab 4 bytes for sharedscreen_protect (chip); remain=451996

Memwatch breakpoints enabled

0: 00DFF000 - 00DFF1FF (512) RWI NONE

1: 00000000 - 001FFFFF (2097152) RWI NONE

TBL MemProtect: address 000298b8 size 00000004, range (000298b8 - 000298bc), bits 00000000

[ 0.03786] Loader: ldr_alloc_permanent: grab 128 bytes for sharedstate (fast); remain=515968

[ 0.03790] Loader: SharedState Fast at 003d4e00 - 003d4e80

[ 0.03792] Loader: ldr_alloc_permanent: grab 206568 bytes for music (chip); remain=245428

[ 0.03793] Loader: ldr_alloc_permanent: grab 78984 bytes for music (fast); remain=436984

[ 0.03794] Loader: Music Chip at 000298bc - 0005bfa4

[ 0.03795] Loader: Music Fast at 003d4e80 - 003e8308

...

I also repurposed an old printf implementation I had lying around and added custom format code to do things like print all the registers in the machine which came in handy in a number of cases.

Memory protection

Once we saw the possibilities of calltraps we started really brewing. What if we could leverage the memory breakpoint functionality of the UAE debugger and control that programatically from the Amiga side? That way we could protect sensitive data in the track loader from stray writes and tackle issues that would normally take hours to debug much more quickly.

Said and done, we did that too. This turned out to be a major time saver for memory smash bugs and stray reads and writes.

The assembly interface is trivial:

MEMPF_READ = $0001

MEMPF_WRITE = $0002

MEMPF_DMAREAD = $0004

MEMPF_DMAWRITE = $0008

MEMPF_ALL = MEMPF_READ | MEMPF_WRITE | MEMPF_DMAREAD | MEMPF_DMAWRITE

; UAEMemProtect address,size,bits

IFD NEWAGE_DEBUG

UAEMemProtect macro

move.l #\3,-(sp)

move.l #\2,-(sp)

move.l \1,-(sp)

jsr $f0ff54

lea.l 12(sp),sp

endm

ELSE

UAEMemProtect macro

endm

ENDC

As you can see from the bit definitions above, we separate memory accesses into four groups:

- CPU reads

- CPU writes

- DMA reads

- DMA writes

This is essential for things like our track loader, which uses floppy DMA. While the DMA is writing to the memory, we don’t want anyone reading it, and vice versa. We made short work of many bugs using this feature, and I don’t think we would have shipped a quality demo without it.

When a memory access faults the protection mask, we break into the UAE debugger on the faulting instruction. This makes it relatively straight forward to solve memory corruption issues:

TBL MemProtect Access Trap

PC: 0x002213bc

Address: 0x00000004

Access: CPU_D_R

Size: 4 bytes

R/W: read

Access Prot: 0x01, Memory Prot: 0x04

-- stub -- activate_console

D0 00000002 D1 00000005 D2 00013488 D3 20FF00C0

D4 003D4E00 D5 000326E8 D6 003D4E80 D7 0021EBB4

A0 00221313 A1 0021BE64 A2 002213DA A3 0021BD24

A4 00F0FF54 A5 00DFF088 A6 00200804 A7 0021BD24

USP 0021BEE0 ISP 0021BD24 SFC 00000000 DFC 00000000

CACR 00000000 VBR 00000000 CAAR 00000000 MSP 00000000

T=00 S=1 M=0 X=0 N=0 Z=0 V=0 C=0 IMASK=0 STP=0

002213C0 4eae fdf6 JSR (A6, -$020a) == $002005fa

Next PC: 002213c4

>

High resolution timers

Another easy calltrap interface we added was to get the number of CPU cycles since the machine powered on. This enables us to do simple scope-based profiling.

High-level timeline profiling

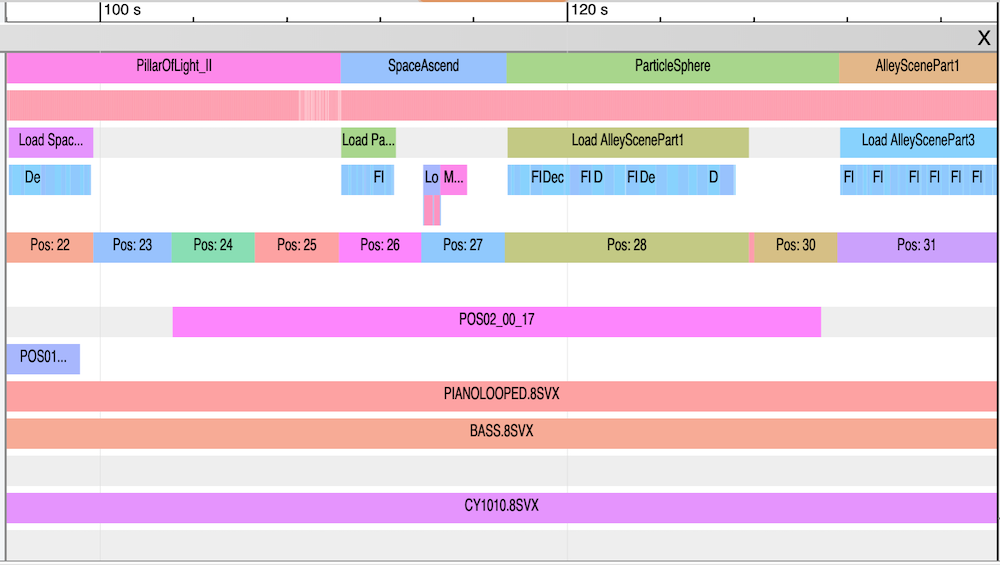

We also added a way to profile the loading, decompression and part timings on a high level using Chrome’s tracing view. Every run in our debug emulator will spit out a trace file compatible with this view.

Some notes to make sense of this:

- The top row shows what part is active

- The next row is frame timings (makes more sense zoomed in)

- The third row is what part the loader is trying to pull in

- The fourth row indicates what kind of activity the loader thread is doing (such as sample decompression, drum mixing, LZ4 decompression, checksumming, floppy DMA etc)

- The next row indicates what pattern we’re at in the song

- Finally the rest of the rows show what samples are in use, to debug issues with samples not coming in on time

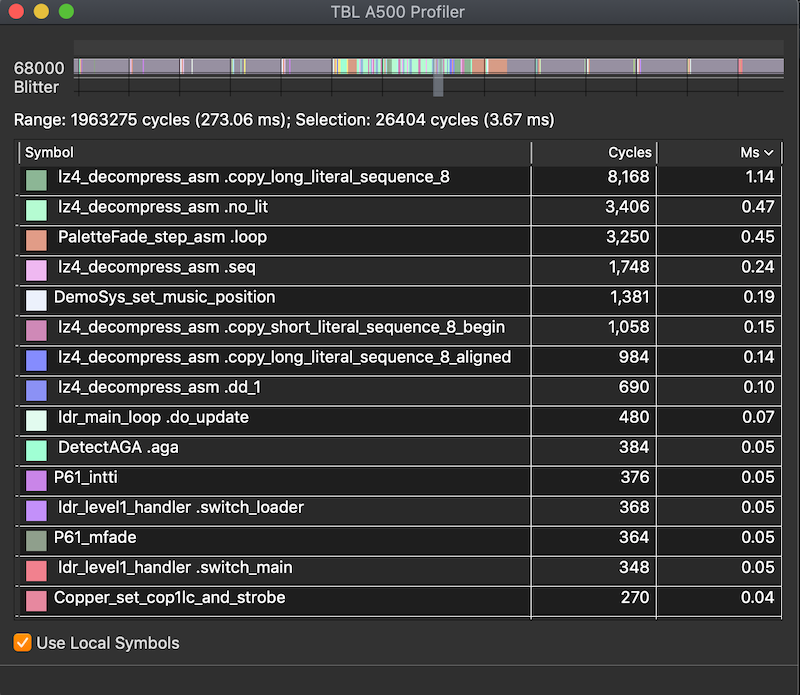

Instruction tracing profiling

We also decided to capture each instruction as it was flowing through the emulator, as well as long symbol data when we switch parts in the demo. This allows us to capture cycle correct profiling data as well as details about blits and other things that are in flight on the machine.

Automatic disk swapping

In debug mode, the emulator swaps disks for you :)

readline interface

This is a small point, but if you spend any significant amount of time with the

UAE command line debugger, it’s a really good idea to give it a readline

interface. This means you keep history between sessions, and you can use

Ctrl+R to reverse-search through the history as well, just like in bash.

uaekick

We use a little script called uaekick to test our work in the emulator. It

has grown over the years and now supports a plethora of options. A couple of

example invocations follow.

Kick off a stock 512+512 A500 configuration, with two floppies in the swap list:

uaekick t2-output/amiga-mac-debug-default/disk?.adf

Kick off a single executable on the same stock A500 config:

uaekick t2-output/amiga-mac-debug-default/TexturedRubberCubeTest

Configure memory on the fly:

uaekick --fastmem=2048 --slowmem=0 path/to/program_or_floppy

Configure kickstart on the fly:

uaekick --kickstart=path/to/kickstart31.rom path/to/program_or_floppy

Switch to an A1200:

uaekick --machine=a1200 --kickstart=path/to/kickstart path/to/kickstart31.rom path/to/program_or_floppy

This is a huge time saver, because you never have to go back and double check that you configured everything correctly.

Asset build pipeline

We use a simple python tool to make sure assets are transformed into binary data we can include in parts. For example, here is the pipeline code for the alley part:

class AlleyScenePart3(PartData):

def __init__(self):

super(AlleyScenePart3, self).__init__('AlleyScenePart3', globals.source_data_root + '/AlleyScene', globals.destination_data_root + '/AlleyScenePart3')

self.image_converter = ImageConverter()

self.alembic_lines_convert = AlembicLinesConverter()

def build_part(self):

self.image_converter.convert_planar_bin_ocs(

self.input_directory + '/AlleyBackgroundNoCar_8Colors_part2.png', self.output_directory, 8)

self.image_converter.convert_amiga_sprite(

globals.source_data_root + '/SwitchFloppy/diskswap2.png', self.output_directory, 16)

self.alembic_lines_convert.convert(

self.input_directory + '/NewAlleyScene_LinesAndCamera_Part2.abc',

globals.source_data_root + '/SpaceAscend/SpaceAscend_Lightning_10.json',

self.output_directory + '/lines.bin')

The data is then crunched as needed to native format for the Amiga side to simply incbin into code.